Reproducible Reporting

Learning Objectives

- Be able to manage computational projects for reproducibility, reuse, and collaboration.

- Use R tools and conventions to document code and analyses and produce reproducible reports.

- Be able to publish, share materials, and collaborate through the web.

- Understand why this all matters!

Suggested Readings

1 Literate programming

Literate programming is a paradigm first introduced by Donald E. Knuth. The idea is simple:

Treat programs as a literature understandable to human beings

The goal is to integrate data analysis (executable code) with textual documentation, linking data, code, and text together in one document. Literate programming can be directly linked to the concept of reproducibility. Basically, for someone to make a legitimate scientific claim, they should at minimum be able to fully reproduce their results from their raw data (and preferrably others should be able to reproduce them as well).

This leads to the idea of having a reproducible workflow - from raw data to published results.

Enter Quarto

Quarto integrates a

documentantion language (markdown) with a

programming language (R1). This enables authors

to craft interactive documents of data, analysis, and results that are

easily shareable, particularly through the web.

Note: You may hear about “RMarkdown” when using Quarto. That’s because RMarkdown was the predecessor to Quarto. Whereas RMarkdown was designed for R, Quarto took the best parts of it, improved it, and made it more accessible by also supporting Python, Observable and Julia.

2 Quarto overview

Watch this ~20-min video to get a quick introduction to Quarto. Trust me - there’s a LOT you can do with Quarto, but you can get most of what you need in just 20 minutes!

3 Elements of Quarto

3.1 Markdown

Markdown is a simple, plain text language for converting raw text to HTML for the web (and other outputs, like pdfs). Some of its attributes include:

- It has a very small syntax (html links, tables, images, headers, italic / bold font, and a few other things).

- It is both easy-to-read and easy-to-write.

- It is clean and legible across multiple platforms (including mobile phones).

- All formatting is handled automatically through a browser.

- Supports raw html as well.

3.2 Code

Code “chunks” are defined through special notation and are executed

in sequence throughout the document (just like an .R

script). You can mix code directly in with markdown (e.g. “Here’s some

simple math in R: 2 + 2 produces 4”) or in separate chunks

before or after markdown text. This enables you to write English

language text in markdown to explain something, and then immediately

follow it up with code to illustrate or demonstrate it.

3.3 Outputs

Quarto enables you to “render” the markdown text and R code into a variety of output formats. The default format is an html document for reading through an internet browser and sharing results across the web. Check out the Quarto Gallery for some examples. Other formats include:

- Articles & Reports

- Presentations

- Interactive Docs

- Websites

- Books

3.4 Publish to the web

Once you’ve written up your Quarto document, you can publish it to the web for free using RPubs: http://rpubs.com/

Watch this quick demo of how to publish your Quarto file to the web using RPubs (Note that this video is a demo of RMarkdown, but it’s essentially the same process with Quarto):

4 Elements of a

.qmd document

4.1 The YAML header

The YAML header contains metadata about the document - most

importantly the output format. Different settings can be set within

different format. Here we’ll be focusing on on the html

format.

It is contained between these separators at the top of the file.

---

---Markdown was originally designed for HTML output, so it may not be

surprising that the HTML format has the richest features among all

output formats. To create an HTML document from R Markdown, you specify

format: html in the YAML metadata of your document:

---

format: htmls

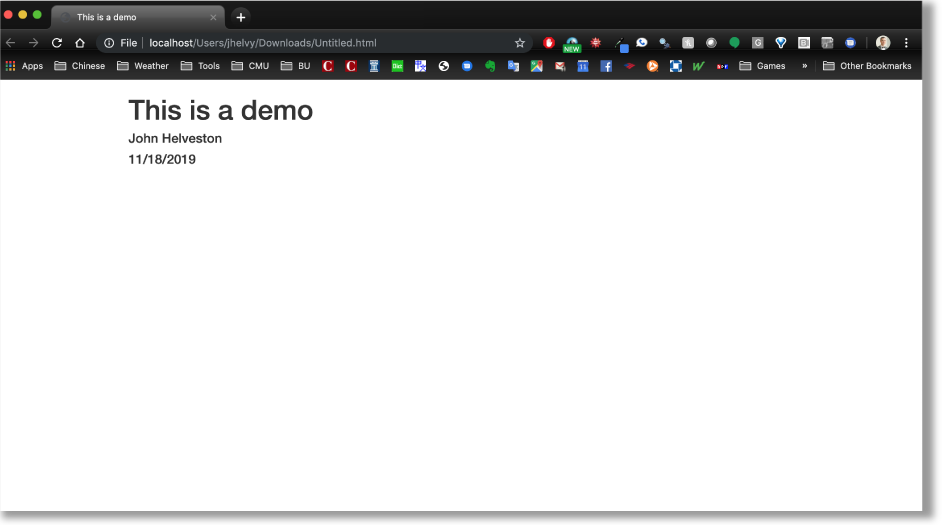

---At a bare minimum, your yaml should include a title and output format. Here I’ve also included my name as the author, and the date:

---

title: "This is a demo"

author: "John Helveston"

format: html

---This will produce an html page that looks like this:

4.2 Markdown basics

The text in an Quarto document is written with the Markdown syntax.

Check out this 60-second markdown reference guide to get the basics

If you’re not sure how to make something in markdown, you can try it out first with this handy markdown demo site.

Here’s some of the most-used markdown syntax:

| Type this… | …to get this |

|---|---|

normal text |

normal text |

*italic text* |

italic text |

**bold text** |

bold text |

***bold italic text*** |

bold italic text |

superscript^2^ |

superscript2 |

~~strikethrough~~ |

|

`code text` |

code text |

For headers, use the # symbol:

# Header 1

## Header 2

### Header 3

#### Header 4

##### Header 5

###### Header 6

To make a bullet list, use the -

symbol:

- first item

- second item

- third item- first item

- second item

- third item

To make a numbered list, use numbers with a period:

1. first item

2. second item

3. third item- first item

- second item

- third item

To make a url link to another site, use brackets with parentheses:

[Download R](http://www.r-project.org/)To make a basic table, use the | symbol

to break up columns, and make a header row by adding

-------- underneath the header row:

Table Header | Second Header

------------- | -------------

Cell 1, 1 | Cell 2, 1

Cell 1, 2 | Cell 2, 2| Table Header | Second Header |

|---|---|

| Cell 1, 1 | Cell 2, 1 |

| Cell 1, 2 | Cell 2, 2 |

Check out this handy online table converter

4.3 Inline R code

You can embed R code directly in a markdown sentence. For example, if

you had already created an object x…

x <- 10…you could use x in a sentence by typing a

` followed by r then any R code you want:

The value of parameter `x` is `r x`, and `2*x` is `r 2*x`The value of parameter x is 10, and 2*x is

20

Wow - that’s pretty cool!

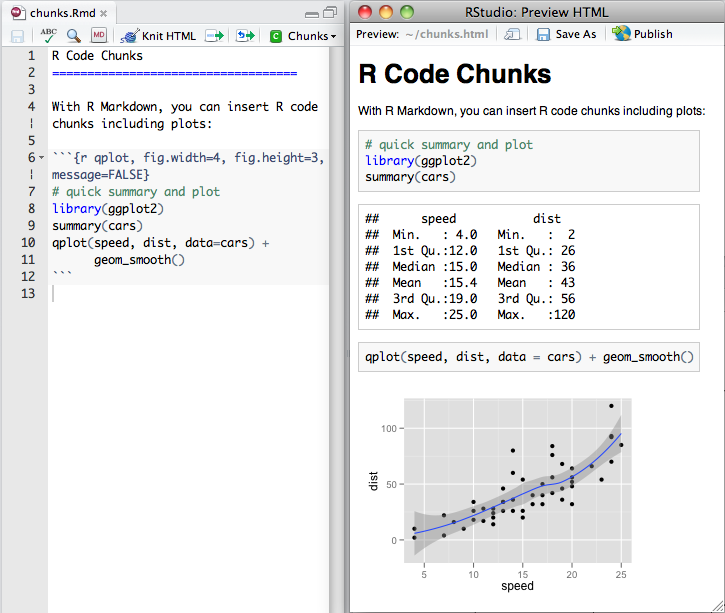

4.4 R Code chunks

Code chunks are blocks of R code that are executed when you compile

the .qmd document. The output of the code is inserted into

the Quarto document. Chunks can be used as a means to render R output

into documents or to simply display code for illustration (e.g. with

option eval=FALSE).

Here’s an example of a .qmd file with a code chunk on

the left and the rendered output on the right:

You can quickly insert an R code chunk with:

- The keyboard shortcut

Ctrl + Alt + I(OS X:Cmd + Option + I) - The Add Chunk

command

in the RStudio toolbar

command

in the RStudio toolbar - By typing the chunk delimiters

```{r}and```.

4.4.1 Chunk notation

In between the chunk delimiters ```{r} and

```, you can write R code:

```{r chunk-name}

cat('hello world!')

```The above R chunk renders as:

## hello world!You don’t have to name the chunks, but it’s a good practice (like commenting your code). In the above chunk, the name of the chunk is “chunk-name”.

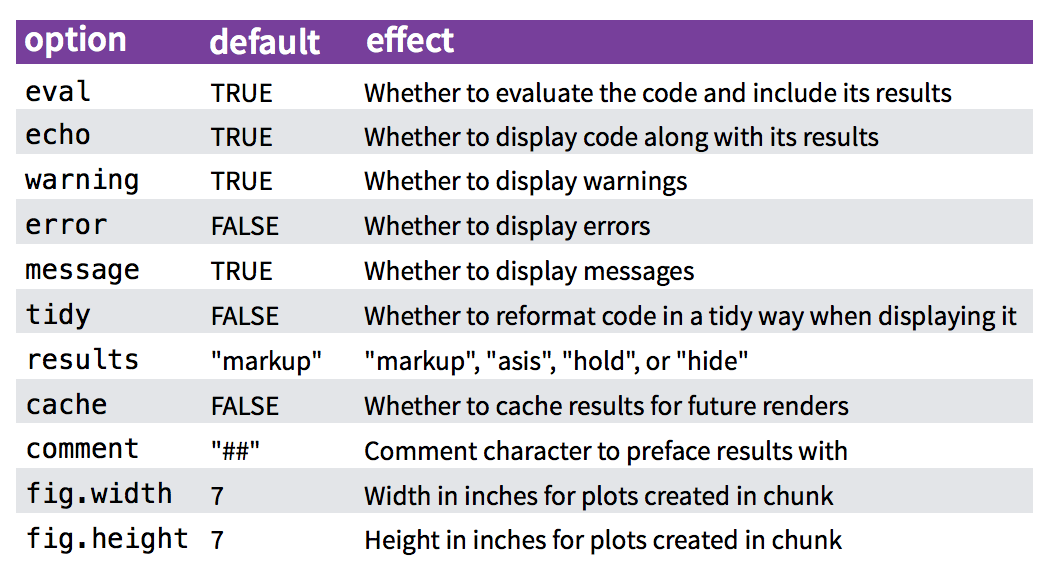

4.4.2 Chunk options

There are lots of options for customizing how markdown chunks appear. By default, code chunks print code + output:

cat('hello world!')## hello world!But you can change this by inserting options immediately after the

r in the header ```{r} and separate them with

commas. For example, if you just want to display the code but don’t want

it to actually run, you can add eval=FALSE:

```{r, eval=FALSE}

cat('hello world!')

```If you only want to print the output (i.e. run the

code, but don’t show the code itself), use echo=FALSE:

```{r, echo=FALSE}

cat('hello world!')

```Finally, if you want to run the code in the background but you don’t

want anything to print, use include=FALSE:

```{r, include=FALSE}

cat('hello world!')

```There are loads of other options for controlling how R chunks behave - here is a list of some (for more details see http://yihui.name/knitr/):

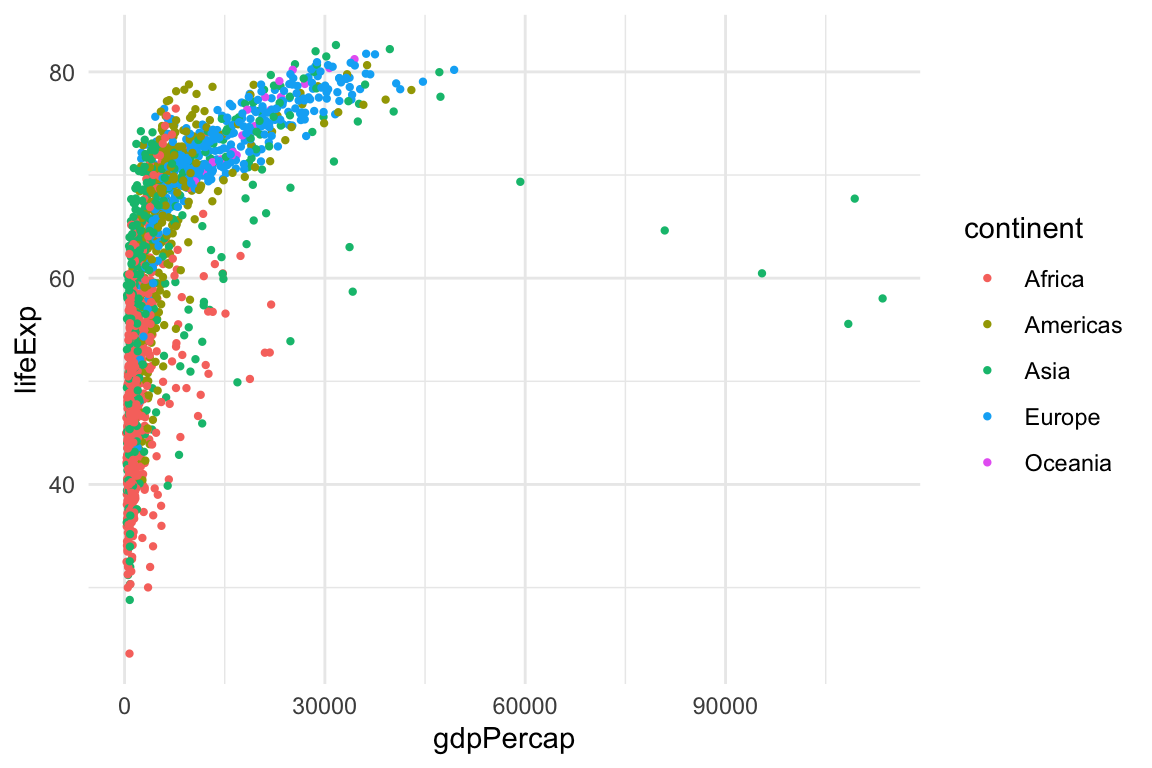

4.5 Plots

By default, figures produced by R code will be placed immediately

after the code chunk they were generated from. Here’s an example using

ggplot2 to plot the relationship between a couple of

variables:

```{r, message=FALSE, fig.height=4, fig.width=6}

library(ggplot2)

library(gapminder)

ggplot(gapminder) +

geom_point(aes(x = gdpPercap, y = lifeExp, color = continent), size=0.8) +

theme_minimal()

```library(ggplot2)

library(gapminder)

ggplot(gapminder) +

geom_point(aes(x = gdpPercap, y = lifeExp, color = continent), size=0.8) +

theme_minimal()

You can adjust the dimensions of plots using fig.height

& fig.width inside the chunk settings. For example, in

the above plot the setting are

{r, fig.height=4, fig.width=6}.

5 Tips

5.1 Rendering to other output formats

As previously mentioned, the default output format for Quarto

documents is html, but you can change this by adjusting the YAML

format. For example, if I wanted to create a pdf document

instead, I could use format: pdf in the YAML:

---

title: "This is a demo"

author: "John Helveston"

format: pdf

---If this doesn’t work for you, chances are you may need LaTeX also installed. You can install a small version of LaTeX with this command in R:

tinytex::install_tinytex()

5.2 Convert a data frame to a table

If you have a table already organized as a data frame in R, rather

than painstakingly type the content into a typical markdown table, you

can just use the kable() function to directly convert it.

Here’s an example using the beatles data frame from the

earlier lesson on data

frames:

beatles <- data.frame(

firstName = c("John", "Paul", "Ringo", "George"),

lastName = c("Lennon", "McCartney", "Starr", "Harrison"),

instrument = c("guitar", "bass", "drums", "guitar"),

yearOfBirth = c(1940, 1942, 1940, 1943),

deceased = c(TRUE, FALSE, FALSE, TRUE)

)

kable(beatles)| firstName | lastName | instrument | yearOfBirth | deceased |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| John | Lennon | guitar | 1940 | TRUE |

| Paul | McCartney | bass | 1942 | FALSE |

| Ringo | Starr | drums | 1940 | FALSE |

| George | Harrison | guitar | 1943 | TRUE |

5.3 Inserting a Python code chunk

One of the most impressive things about Quarto code chunks is that

the code itself doesn’t have to be R code. For example, if you want to

use Python code instead, just change {r} to

{python} in the code chunk:

```{python}

'In Python, you can concatenate strings' + ' like this!'

```The above chunk renders as:

## 'In Python, you can concatenate strings like this!'Page sources:

Some content on this page has been modified from other courses, including:

Actually Quarto supports 4 programming languages: R, Python, Observable, and Julia.↩︎